I recently published a Washington Post op-ed called "Deficits do Matter" that was co-authored with talk-show host, commentator and former Congressman Joe Scarborough. The piece argues that high and rising levels of public debt are a real concern. It also makes the case that the stimulus packages that began in 2009 --which have consisted mainly of temporary tax cuts and transfer payments -- have significantly raised the public debt while doing very little to solve the nation's long-term employment and growth problems.

That op-ed and others I've recently written have discussed the policy recommendations of Professor Paul Krugman, a Princeton economist and New York Times columnist. While I have tremendous respect for Professor Krugman, since 2008 he and I have disagreed consistently over the approaches needed to get the U.S. economy on the road to a real and sustained recovery. I've also spelled out my views in detail in my book The Price of Civilization (2012).

I have argued against short-term stimulus packages. Krugman has supported them, and indeed argued that they should have been even larger. I have been against temporary tax cuts and temporary spending programs, believing that instead we need a consistent, planned, decade-long boost in public investments in people, technology, and infrastructure. Such a sustained rise in public investment should have been paid for by ending the Bush-era tax cuts in 2010, or by adopting a comparable boost in revenues. Instead Obama and Congress have now made almost all of those tax cuts permanent, putting us into a deeper fiscal bind.

Yesterday, Krugman responded to my recent op-ed by digging in deeper on the deficit question. He argued yet again that the U.S. can and should incur more debt to pay for a short-term boost in aggregate demand. While he did not lay out a quantified plan (that has been the case from the start, so it's hard to know exactly what Krugman has in mind in a quantitative sense), the CBO has recently estimated that without the recent deficit-reduction actions of the White House and Congress, the public debt would rise to around 87 percent of GDP in a decade. I presume that Krugman would support that trajectory or something like it (he should tell us by now what path of deficits he actually recommends).

Let me address his points here in detail.

First off, here is what I mean when I say that Krugman is a crude Keynesian: he takes a simplistic and inadequate version of the Keynesian economic approach as his guide for budget policy. Keynes himself was far subtler. In 1937, with British unemployment still around 10 percent, Keynes wrote: "But I believe that we are approaching, or have reached, the point where there is not much advantage in applying a further general stimulus at the centre." He believed, for example, that more structural policies were needed to address the continued unemployment.*

There are four elements of crude Keynesianism and, indeed, of Krugman's position:

(1) The belief that multipliers on tax cuts and transfers are stable, predictable and large;

(2) The belief that America's employment and growth problems are overwhelmingly cyclical, not structural, and therefore remediable by short-term aggregate demand management;

(3) The belief that a growing debt burden is a minor nuisance as long as the economy is in recession;

(4) The belief that for practical purposes, the most urgent need is to raise aggregate demand rather than to focus on the quality and type of public spending.

I believe that all of these positions are misguided.

First, Krugman believes that fiscal multipliers are predictable and large. Thus, a $1 rise in government spending of any kind, according to Krugman, predictably leads to something like $1.50 in higher GDP. Similarly, a $1 cut in payroll taxes leads to something like a $1.30 rise in GDP.

The belief in stable, predictable, and large multipliers is belied by both theory and evidence. Households and local governments might simply use a temporary tax cut or temporary transfer, for example, to pay down debts rather than to increase spending, especially because the tax cut or transfer is seen to be temporary. Businesses, concerned about the buildup of public debt, might hold back on business investment in the face of large deficits, anticipating higher taxes in the future.

The original stimulus legislation was overwhelmingly of the form of temporary tax cuts and temporary transfer payments, the kind of deficit spending especially likely to have little effect on aggregate demand. Only $88 billion of the $787 billion stimulus-package was in direct purchases of goods and services by the federal government. The rest was temporary transfers and tax cuts.

(This was not an accident. A critical and predictable weakness of the 2009 stimulus is that House Democrats and the White House negotiated it in just a few weeks. In the unnecessary haste, there was no serious consideration given to long-term needs in infrastructure, for example. With presidential leadership we could -- and should -- have forged a decade-long strategy. Now we have no such strategy in place or likely to come into place.). Later stimulus packages (such as the 2010 two-year extension of the Bush tax cuts) have been even more weighted towards temporary tax cuts.

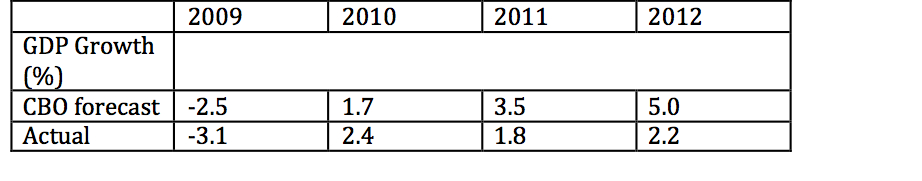

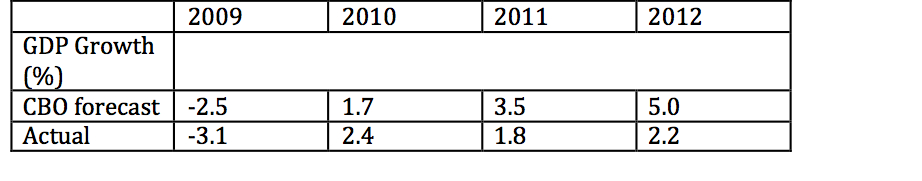

The Keynesian theory is that the stimulus would raise output and employment while the economy naturally returned fairly quickly to full employment and rapid growth from the cyclical downturn. This long-term recovery did not occur as projected. Growth has not resumed on a normal basis. The Keynesian CBO model failed very badly to track the U.S. economy.

Here is the CBO forecast made in mid-2009 and the actual growth outcomes:

Why has the CBO model failed so badly? There are of course many theories. Krugman argues that the stimulus worked just as advertised, with the multipliers that were predicted, but that other factors held up recovery. He does not present a quantified model, so doesn't really account for the shortfall of the CBO Keynesian modeling. My own view is that the

predicted multipliers were too high in the first place, especially for such a poorly designed tax-and-transfer program, and that recovery is impeded by structural factors. These structural components are not susceptible to a Keynesian diagnosis or to a Keynesian remedy. They require a long-term public investment response that has not been forthcoming.

Second, Krugman seriously and repeatedly downplays these structural changes occurring in the U.S. economy. He repeatedly emphasizes that we suffer a demand shortfall, pure and simple, one easily remedied by more stimulus. Yet it's increasingly hard to reconcile many features of the U.S. economy with this view.

Unlike the Great Depression, which Krugman repeatedly uses as his reference point, U.S. profits are soaring. Unlike the Great Depression, the world economy is growing rather rapidly (3 to 4 percent per year) so that more rapid U.S. export growth is feasible. Unlike the Great Depression, vacancy rates are recovering even as unemployment is stuck. (Technically, the Beveridge Curve has shifted to the right.)

The CBO also suggests that much of the slowdown in GDP growth after 2002 is the result of a slowdown in the growth of potential GDP. According to CBO, potential GDP growth was 3.1 percent per year during 1991-2001, but slowed to just 2.2 percent per year during 2002-2012.

What are some of the structural problems? These include large-scale offshoring of jobs, large-scale automation of jobs, decline in demand for low-skilled workers, skill mismatches, broken infrastructure, and rising global energy and food prices. These require various kinds of targeted public investment spending, not simply aggregate demand.

In view of these challenges, would a different kind of spending program have worked better? If the spending had been concentrated on long-term infrastructure and job skills, with investments carried out not for two years but over the course of a full decade (as in the 1950s-60s national highway program), the answer is probably yes. But such projects were not "shovel ready."

Such long-term investment programs are very different from quick-and-dirty Keynesian "stimulus" packages such as temporary tax cuts. Long-term investment programs require thinking and planning of the kind that has never happened with Obama's stimulus packages. Examples of long-term federal investment programs include the national highway system, the moon program, and the human genome project. A massive renewable energy program - R&D, renewable power generation, new transmission grid, urban smart grids, and related infrastructure (e.g. for electric vehicles) - is an example of what is needed over the course of a decade. It might have been feasible in 2009 when Obama had the upper hand and the momentum. It is, alas, very unlikely today.

The Administration should indeed have taken several months in 2009 to design and advocate for long-term investment programs for renewable energy, fast intercity rail, large-scale highway upgrading, large-scale skill and job training, and so forth, rather than rushing to pass a stimulus package of hundreds of billions of dollars of shortsighted and largely ineffective temporary tax cuts and transfer programs. The budget should have paid for such new long-term investments by allowing the temporary Bush-era tax cuts to expire on schedule in 2010 (or by negotiating equivalent revenues of 2-3 percent of GDP per year as the price for maintaining the Bush-era tax cuts).

One of the Obama arguments at the time was that the rush in the stimulus program was needed to avoid a Great Depression. This was and is highly doubtful (though, yes, it is widely accepted). The US economic emergency in late 2008 and early 2009 wasn't really an aggregate demand crisis but a financial crisis. The chaotic failure of Lehman Brothers had led to an intense panic and credit squeeze. The Fed therefore needed to flood the markets with liquidity, which it rightly did, in order to unwind the panic. The Fed's action was the real difference with 1933 (when the Fed allowed the banks to fail). It was the Fed, not the fiscal stimulus, which prevented a fall into depression.

Third, crude Keynesians like Krugman believe that we don't have to worry about the rising public debt for many years to come, perhaps well into the next decade. This is remarkably shortsighted. The public debt has already soared, from around 41 percent of GDP when Obama came into office to around 76 percent of GDP today (and with no lasting benefit to show for it). If Krugman had his way, and deficits were not restrained, the debt-GDP ratio would already be above 80 percent by now and would be rising rapidly towards 90 percent and above (as shown in the recent CBO alternative scenario).

Krugman now writes: "everyone repeat with me: there is no deficit problem." He says, in effect, that since the debt-GDP ratio is now likely to be stable at around 75%, we need not worry. But his claim is thoroughly misleading. The forecast of a stable debt-GDP ratio is precisely because Washington has rejected Prof. Krugman's advice. If DC instead followed his advice, the debt-GDP ratio would indeed already be significantly higher and would be rising rapidly.

It's true that we've not paid heavily so far for this rising debt burden because interest rates are historically low. Yet interest rates are likely to return to normal levels later this decade, and if and when that happens, debt service would then rise steeply, increasing by around 2 percent of GDP compared with 2012. Many people seem to believe that we can worry about rising interest rates when that happens, not now, but that is unsound advice. The build-up of debt will leave the budget and the economy highly vulnerable to the rise in interest rates when it occurs. The debt will be in place, and it will be too late to do much about it then.

According to the new CBO baseline, debt servicing within a decade is now on track to be around 3.3 percent of GDP, larger as of 2023 than the total of all non-defense discretionary spending and also all defense spending in that year! This high interest servicing cost will be the result of the large build-up of debt in recent years combined with the return of interest rates to historically normal levels. As interest service costs rise, vital public investments and other programs are likely to be shed. That's when we'll suffer the most severe fiscal consequences of our debt buildup of debt. Of course neither Prof. Krugman nor his followers seem to be much interested in looking ahead a few years.

In his first blog response to me, Krugman argues that the coming rise in debt servicing in the CBO baseline is somehow irrelevant because it will result from a rise in interest rates not from a continuing rise in the debt-GDP ratio. But he has missed the point. As a nation we should prepare sensibly for a return to normal interest rates in the future. The huge amount of debt that we've already taken on (not to mention the added debt that Prof. Krugman would like us to take on) makes the future budget very vulnerable to a return of interest rates to normal.

Fourth, crude Keynesians believe that for all intents and purposes, "spending is spending." Yes, Prof. Krugman acknowledges waste and all of that, but says that for aggregate demand reasons it is better to spend now on the waste than to cut wasteful spending. Here's the discussion on Charlie Rose the other day.

KRUGMAN: "Basically, any kind of spending cut right now is going to hurt the economy. Now -- "

ROSE: "Whether it's entitlements or not?"

KRUGMAN: "Whether it's entitlements or not. Even if it's defense, even if it's wasteful defense spending, it's going to hurt the economy if you cut it right now. It doesn't mean that we shouldn't look for ways to cure waste but right now to a large effect, spending is spending. So, do the kind of reform I want, and stop overpaying for Medicare, stop paying for unnecessary treatments. That's clearly what we want to do in the long run. But right now, it's going to mean less income for hospitals -- that is going to be a problem for the economy."

This approach is disastrous both politically and economically. Progressives like myself believe strongly in the potential role of public investments to address society's needs - whether for job skills, infrastructure, climate change, or other needs. Yet to mobilize the public's tax dollars for these purposes, it is vital for government to be a good steward of those tax dollars. To proclaim that spending is spending, waste notwithstanding, is remarkably destructive of the public's trust. It suggests that governments are indeed profligate stewards of the public's funds.

Yet it's even worse on the economic front. Spending is not spending. The U.S. needs productive public investments, not wasteful spending. We need to modernize our infrastructure, retool our energy system, make our cities more resilient, and help to train a new productive labor force. All of that is hard work. It requires careful government programs, working alongside the private sector, and good coordination with state and local governments. It requires facing down vested interests in both parties all too happy to continue the wasteful ways.

Keynesians ignore or even disdain this kind of hard budget work. Just spend and cut taxes, we are told, and the economy will recover and go back to normal. Sad.

So, to summarize, what is crude Keynesianism?

(1) The belief in large, stable, and predictable multipliers on taxes and transfers;

(2) The belief that our problems are due overwhelmingly to a deficiency of aggregate demand, rather than to structural problems that need a long-term approach;

(3) The belief that a rapidly rising debt-GDP ratio is largely benign because interest rates are low today and will stay so indefinitely;

(4) The belief that "to a large effect, spending is spending," thereby catering to waste and vested interests while ignoring America's urgent investment needs.

In my view the result of this misguided approach, adopted by the Obama Administration, has been a large build-up of public debt with no long-term benefits for an economy that instead needs a public-investment-led recovery. If we had followed Mr. Krugman's long-standing advice to double down on this failed approach the situation would have been even worse. Yes, Mr. Krugman, I believe that you are a crude Keynesian at a time when we need subtler, surer, longer-term policies.

That subtler set of policies should include:

(1) Decade-long public investment programs in renewable energy, upgraded public infrastructure, fast rail, job training and the like;

(2) Adequate fiscal revenues (including tolls on infrastructure) to pay for these investments over the course of a decade, including a downward path of the debt-GDP ratio;

(3) Increased revenues through taxation on high net worth, financial transactions, high incomes, capital gains and carried interest, offshore corporate earnings, and carbon emissions, and a stiff crackdown on tax havens and phony transfer pricing.

All of this would have been much easier if Obama had started down this long-term path in 2009, and had never conceded the permanence of the Bush-era tax cuts for almost all households. Instead, he followed a populist and shortsighted policy of "stimulus" and tax cuts.

*Keynes wrote that, "the evidence grows that -- for several reasons into which there is no space to enter here -- the economic structure is unfortunately rigid," therefore requiring more targeted public spending.

?

?

?

Follow Jeffrey Sachs on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JeffDSachs

"; var coords = [-5, -72]; // display fb-bubble FloatingPrompt.embed(this, html, undefined, 'top', {fp_intersects:1, timeout_remove:2000,ignore_arrow: true, width:236, add_xy:coords, class_name: 'clear-overlay'}); });

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jeffrey-sachs/professor-krugman-and-cru_b_2845773.html

BET Awards 2012 declaration of independence 4th Of July 2012 Zach Parise Spain Vs Italy Euro 2012 Pepco erin andrews